As winter fades away and nature awakens, one can’t help but marvel at the colors and delicate blooms of our surroundings. Among the many spring flowers is the Marsh Marigold (Caltha palustris). With its vibrant yellow petals and lush green leaves, this lovely perennial is a true symbol of the changing seasons that can enchant any nature lover, but it is crucial to understand that this alluring beauty harbors a secret: it contains poisonous compounds.

Common Names:

The Marsh Marigold goes by several common names across different regions. In addition to Marsh Marigold, it is often people refer to it as Kingcup due to the resemblance of its cup-shaped flowers to a royal chalice. Furthermore, Sometimes naturalists call it Cowslip of the Marsh, although it is distinct from the true Cowslip (Primula veris). These various names reflect the plant’s widespread popularity and recognition.

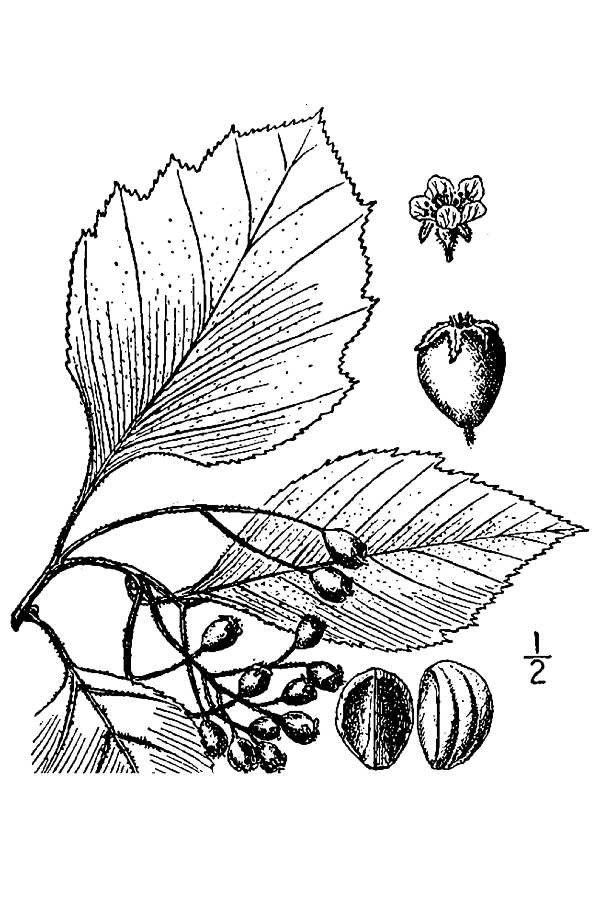

Description:

Marsh Marigold is known for its bright, golden-yellow flowers that bloom in early spring, typically between March and May, depending on the region. The flowers have a distinct cup shape with five to nine overlapping petals. They can reach a diameter of around 2 to 5 centimeters (0.8 to 2 inches). The glossy, dark green leaves of the Marsh Marigold are rounded or heart-shaped and are borne on long stalks emerging from the base of the plant. This perennial herb grows to a height of about 30 to 90 centimeters (12 to 35 inches).

Territory:

Marsh Marigold is native to Europe, Asia, and North America. In Europe, it can be found throughout the continent, from the British Isles to Scandinavia and down to the Mediterranean region. In Asia, its range extends from Siberia to Japan. In North America, Marsh Marigold is distributed across Canada and the northern United States, particularly in wetland areas.

Habitat:

Just like Cattails, Marsh Marigold thrives in wet and marshy habitats, displaying a preference for shallow water bodies such as ponds, ditches, swamps, and damp meadows. It is commonly found near streams and rivers, where it benefits from the constant moisture. The plant can tolerate partial shade but generally prefers full sun. Its adaptability to various soil types, including clay, loam, and sandy soils, contributes to its wide distribution.

Poisonous Components:

The Marsh Marigold contains toxic compounds, primarily protoanemonin, which is a potent irritant. Protoanemonin is released when the plant is damaged or crushed, making it potentially harmful to humans and animals alike. While the entire plant contains varying levels of protoanemonin, the highest concentrations are typically found in the fresh leaves and stems. The roots and seeds also contain trace amounts of this toxic compound, albeit in smaller quantities.

Symptoms of Poisoning:

If the Marsh Marigold is ingested or comes into contact with the skin or eyes, it can lead to various symptoms of poisoning. These symptoms include blistering, skin irritation, redness, swelling, and burning sensations. Ingestion of the plant can cause nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain, and in severe cases, even respiratory distress. It is important to note that the intensity of the symptoms can vary depending on the individual and the amount of exposure to the toxic compounds.

Marsh Marigold Conservation Status:

The conservation status of the Marsh Marigold is a matter of concern. While it is not globally threatened, this species faces certain challenges, as does the broadleaf arrowhead, due to habitat loss and degradation. Wetland destruction, pollution, and invasive species pose significant threats to its survival. Additionally, over-harvesting for ornamental purposes can further impact the population of this plant in the wild. It is crucial to raise awareness about the importance of conserving wetland habitats and protecting the Marsh Marigold along with other flora and fauna that depend on these ecosystems.

Notes of Interest:

- Historical Uses: Despite its toxicity, Marsh Marigold has been utilized in traditional medicine for centuries. It was employed for treating various ailments such as skin conditions, rheumatism, and even as a diuretic.

- Symbolic Meaning: Marsh Marigold is often associated with rebirth and renewal. Its bright yellow flowers herald the arrival of spring, symbolizing hope, and new beginnings.

- Ecological Role: This plant plays a vital role in wetland ecosystems. Its flowers provide a valuable source of nectar for pollinators, while its foliage offers shelter for small aquatic organisms.

Marsh Marigold (Caltha palustris) is a captivating wetland plant that should be admired from a safe distance due to its poisonous nature. While it possesses a certain allure, caution should be exercised when encountering this plant to avoid any potential harm. Understanding its toxicity and taking steps towards preserving its habitat will ensure the continued existence of this species for future generations to appreciate.

Marsh Marigold Look-Alikes:

- Lesser Celandine (Ranunculus ficaria): One of the most common plants mistaken for marsh marigold is the lesser celandine. Both plants belong to the same family, Ranunculaceae, and share a similar yellow flower color. However, there are notable differences in their leaves and habitats. While marsh marigold thrives in wetland areas and has round, kidney-shaped leaves, lesser celandine prefers drier habitats and displays heart-shaped leaves. According to the Royal Horticultural Society (RHS), the two plants can sometimes be found growing alongside each other, contributing to the confusion (RHS).

- Kingcup (Caltha palustris var. radicans): Another plant closely related to the marsh marigold is the kingcup, which is a subspecies of Caltha palustris. Kingcup resembles marsh marigold so closely that the two are often considered synonymous. The primary difference lies in the habitat: while marsh marigold is found in marshes and wetlands, kingcup typically inhabits damp meadows and woodland areas. However, due to regional variations, the terms marsh marigold and kingcup are sometimes used interchangeably, leading to further confusion (Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh).

- Globe Flower (Trollius spp.): Globe flowers, belonging to the Trollius genus, are often mistaken for marsh marigolds due to their similar appearance. Both plants share the characteristic yellow, buttercup-like flowers, and grow in similar habitats. However, globe flowers can be distinguished by their more rounded petals and taller stature compared to marsh marigold. The Royal Horticultural Society notes that globe flowers are commonly found in mountainous regions and prefer cool, moist conditions (RHS).

- Cowslip (Primula veris): Cowslips, while not as like marsh marigolds as the previously mentioned plants, can still occasionally be confused with them. Both species exhibit vibrant yellow flowers and bloom in early spring. However, cowslips have a more delicate appearance, with smaller flowers growing in clusters atop slender stems. Moreover, cowslips prefer drier habitats, often gracing meadows, and grasslands. In contrast, marsh marigolds favor wet and marshy areas (Wildlife Trusts).

Citations:

- Missouri Botanical Garden: Caltha palustris. Available at: https://www.missouribotanicalgarden.org/PlantFinder/PlantFinderDetails.aspx?kempercode=c177

- The Wildlife Trusts: Marsh-marigold.

- USDA Plants Database: Caltha palustris. Available at: https://plants.usda.gov/core/profile?symbol=CAPA8

- Royal Horticultural Society: Caltha palustris. Available at: https://www.rhs.org.uk/plants

- New Zealand Plant Conservation Network. (n.d.). Caltha palustris. Retrieved from https://www.nzpcn.org.nz/flora/species/caltha-palustris/

- Plants For A Future. (n.d.). Caltha palustris – L. Retrieved from https://pfaf.org/user/Plant.aspx?LatinName=Caltha+palustris

- Pouliot, M., & Chamberland, C. (2012). Poison